As a professional cellist, she knows that this child will jeopardise her employment, and she has an inkling that looking after her owl-baby will infringe upon her sense of self.

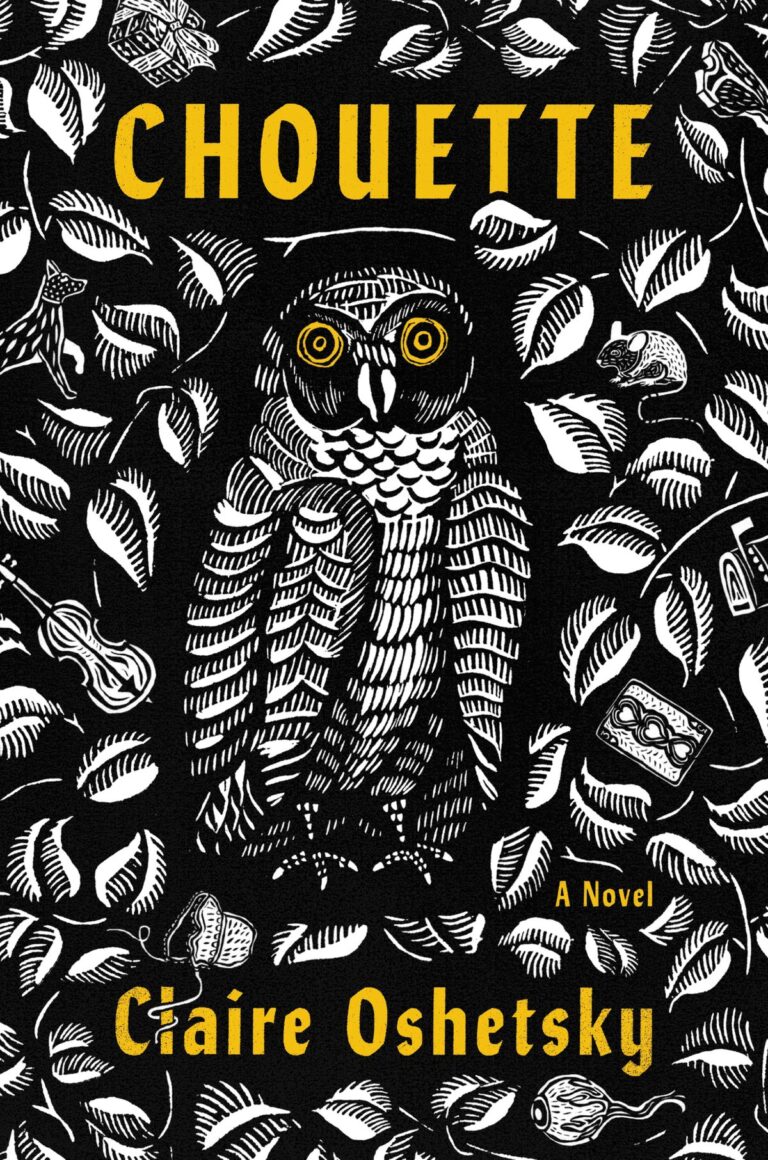

At this stage, Tiny is not sure whether she wants to keep her owl-baby. From the beginning, she is certain that she has been impregnated not by her husband – as everyone, including him, assumes – but by her owl lover: “You may wonder: How could such a thing come to pass between woman and owl? I, too, am astounded, because my owl-lover was a woman.” Already, the reader has a sense of the bizarre tilt of the narrative, which lends a fairy tale-esque feel to the story. Yet, if I were only to use this word, it would not capture the tenderness found within the novel’s pages, nor the artistry, nor even the exhilaration of reading it.Ĭhouette opens with Tiny’s discovery that she’s pregnant, and the whole story is narrated to her owl-baby. Wild for the wilderness and for the gloaming which seeps into every page despite the novel’s ostensibly urban setting wild for the lack of inhibitions, the animalistic instincts of the eponymous Chouette and sometimes her mother Tiny and wild for the sheer wackiness of Oshetsky’s imagination. If I were to describe Claire Oshetsky’s Chouette (2022) in one word, it would be wild.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)